Hey! Guys, in the field of network, we deal with the Ping command every day. But have you really mastered it?

For example, in the same VLAN, can two machines in different network segments be pinged? What exactly is the computer doing when pinging a non - existent IP?

These seemingly simple questions hide a lot of underlying logic of network communication. Let's discuss them in detail today.

For more information, please scan the WhatsApp QR code below to contact customer service.

Can devices in the same VLAN but different network segments be pinged?

Let's start with the basics: for devices in the same VLAN but different network segments, can they be pinged?

Take two computers as an example. The IP of computer A is 10.1.1.1/8, and that of computer B is 11.1.1.1/8. Both are in the same VLAN.

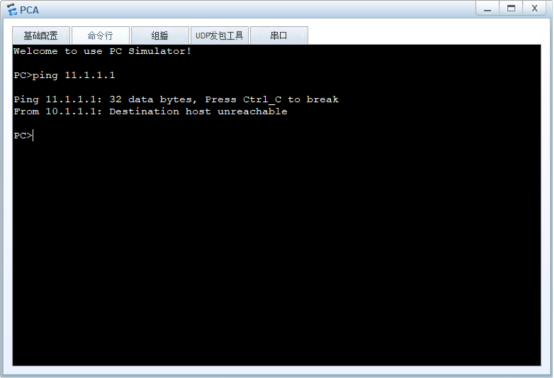

If neither of the two machines sets a gateway, when A pings B, it will directly report "Destination host unreachable". Why? Because A finds that B is not in the same network segment as itself and wants to forward the packet through the gateway. However, since no gateway is set at all, the data packet cannot be sent out at all, and B cannot capture any packets either.

What changes will occur if the gateway is set to the other party's IP

or one's own IP?

If the gateway of A is set to the IP of B, and the gateway of B is set to the IP of A, hey, something amazing happens - it can be pinged!

By capturing packets, it becomes clear: A will first send an ARP broadcast, asking for the MAC address of 11.1.1.1. Since B is in the same VLAN, when it receives the broadcast and sees that this is its own IP, it immediately responds to the ARP. Once both sides know each other's MAC, they can naturally communicate.

What is the computer secretly doing when pinging three non - existent IPs?

However, these are all special cases. Let's try another way of doing it - set the gateway to be "normal", and then ping three non - existent IPs to see what the computer is really thinking.

First, set the gateway of A to itself, and then ping three IPs: one is in the same network segment as A (for example, 10.1.1.2), one is in the same network segment as the gateway (for example, 11.1.1.2), and one has nothing to do with either (for example, 100.1.1.1).

The results are all time - outs, but packet - capturing can reveal some insights: the ARP broadcasts sent by A directly ask for the MAC addresses of these three target IPs without looking for the gateway at all. Since the gateway is set to itself, the computer thinks "there's no need to look for the gateway, just ask the target directly", but the targets don't exist, so naturally there is no response.

But if the gateway of A is set to the IP of B (11.1.1.1), and the gateway of B is set to a non - existent IP (such as 100.1.1.1, which is in a different network segment from anyone else), the situation will change.

When A pings an IP in the same network segment as the gateway (such as 11.1.1.2), it will first send an ARP to query the MAC of the gateway 11.1.1.1. After B receives it, it will respond, but the target IP does not exist, and it will eventually time out. The process of pinging an IP that has nothing to do with anyone is similar. First, query the gateway MAC. B responds, but the target is unreachable, and the result is still a timeout.

The most interesting thing is that the IP (11.1.1.1) of Ping B is also unreachable! Logically, both A and B should be able to obtain each other's MAC through ARP. Why is it unreachable? By capturing packets, it is found that A has indeed received B's ARP reply, but B has been sending ARP broadcasts to query the MAC of its gateway 100.1.1.1. If it doesn't receive a reply, it keeps waiting, so naturally it can't respond to A's Ping.

Ultimately, there is a basic principle in computer communication: when communicating with an IP in a non - local network segment, the MAC of the gateway must be checked first. If the MAC of the gateway cannot be obtained, even if the MAC of the target IP is known, normal communication is not possible. In the previous cases where communication was possible, it was just a coincidence that the gateway was set to the target IP or itself, allowing the computer to take a shortcut.

These seemingly convoluted experiments actually conceal the underlying logic of network communication. Once you understand these, the next time you encounter a situation where Ping is unsuccessful, you will know to start troubleshooting from aspects such as the ARP table, gateway settings, and network segment division. After all, no matter how many strange things happen in the network, you can always find the answer by tracing back to the source.

For more ping resources, follow the Facebook account & youtube account: Thinkmo Dumps